Home > Online Magazine > Online Magazine: Edition 81 - Spring (Sep-Nov) 2024 > Seventh-day Adventist Identity (Deed or Creed) (by Dr Rick Ferret)

Seventh-day Adventist Identity (Deed or Creed)

by Dr Rick Ferret

"Throughout the history of the Christian Church, believers have found it hard to accept this double-edged sword--that true religion clings to the old that proves to be truth but reaches out also for new, more appropriate understandings." [1]

If you approached a Seventh-day Adventist from any region of the world and asked them what constitutes their religious identity, it would be fair to suggest that the majority would frame their response in relation to what they believe. For example, "I believe in the Sabbath and the soon coming, literal return of Jesus, and those concepts are inherent in the name, Seventh-day Adventist." It would be of interest if any Adventist would initially respond by declaring that their church is a multi-national movement with large organizational and institutional (educational, medical, publishing etc) structures that appear to be succeeding in today's society but would also appear very foreign to our pioneers.

If you approached a Seventh-day Adventist from any region of the world and asked them what constitutes their religious identity, it would be fair to suggest that the majority would frame their response in relation to what they believe. For example, "I believe in the Sabbath and the soon coming, literal return of Jesus, and those concepts are inherent in the name, Seventh-day Adventist." It would be of interest if any Adventist would initially respond by declaring that their church is a multi-national movement with large organizational and institutional (educational, medical, publishing etc) structures that appear to be succeeding in today's society but would also appear very foreign to our pioneers.

Ellen White envisaged that the establishment of organisations and institutions would prepare people spiritually, physically and mentally for the imminent Parousia (regardless of how short or long imminent might be interpreted to mean). In other words, SDA institutions were established as a "means to an end." Institutions (forms) were erected to promote and maintain SDA beliefs (content) in the context of the approaching end of this world. While SDA institutionalism has created space and justification for their separation from secular society, therefore, it has also diminished their distinction from the world and questioned the derivation of their identity.

What I find interesting is that this developing ideological shift from an imminent to a delayed Advent has brought in its wake the seeds of tension between sectarian isolation and social concern; between doctrine and deed; between preaching and teaching imminence and occupying till the Lord returns. Think about it, whereas the core Millerite teaching focused on an imminent Second Advent, the heirs of Millerism have been required to juggle imminence with occupancy. Thus, while Adventists continue to maintain a belief in the imminent Parousia, that belief is now diluted with the reality that the time of their earthly sojourn remains indefinite.

Herein lies an ongoing paradox for Adventism. In its original desire to construct unique institutions conducive to separation from the world as a result of Ellen White's counsel and then to utilise those same institutions to evangelise the world, Seventh-day Adventism has become poised between two conflicting extremes. The means (institution building) adopted in the attempt to reach Adventism's desired end (successful evangelism) appears to have denied the movement's explicit reason for its existence (preaching the imminent Parousia). A major dilemma facing Seventh-day Adventism, therefore, is whether temporal goals are actually displacing ultimate Advent goals.

While Adventism appreciates the value of its various institutions in supporting the work of the church throughout the world, it has been far more reluctant to consider the impact that institutionalisation continues to exert on its identity. Reality suggests that contemporary SDA organisational and institutional forms and characteristics may well have outgrown (at least implicitly) Adventism's beliefs that continue to be used as the sole method of measuring the movement's identity.

Robin Theobald was perceptive in assessing the ongoing tension within Adventism when declaring:

"For a movement which still formally commits itself to a belief in the imminent end of things . . . extensive this worldly involvement, particularly in institutions and activities which are directed to the preservation and improvement of mortal existence, would seem to pose something of a paradox." [2]

An inherent danger in maintaining an abstract theological assessment of SDA identity is that it minimises or ignores the movement's socio-historical and cultural contexts. In other words, theological idealism is often divorced from concrete historical reality, resulting in identity distortion. It is apparent that the SDA movement is both a social reality and a divinely commissioned community and these concepts will be explored in relation to Adventist identity in the ensuing pages.

Seventh-day Adventist Identity: Originating Charisma

Institutionalization is a necessity for religious movements (at least those that wish to expand or live beyond the first generation) but also detrimental to those movements. Any analysis of the effects of institutionalization should observe not only what it does for the church but also what it does to the church. Another question (essential for faith-based enterprises) is whether the evolution of a religious movement can be adequately analyzed without critiquing the dimensions of both belief and that of structure?

Institutionalization is a necessity for religious movements (at least those that wish to expand or live beyond the first generation) but also detrimental to those movements. Any analysis of the effects of institutionalization should observe not only what it does for the church but also what it does to the church. Another question (essential for faith-based enterprises) is whether the evolution of a religious movement can be adequately analyzed without critiquing the dimensions of both belief and that of structure?

As mentioned above, to construct a religious movement's identity solely on its belief system is inadequate, for theological perspectives require measurement in real time. In other words, belief systems are abstract definitions which can be maintained indefinitely without regard to a movement's socio-historical and cultural contexts. Other disciplines including sociological, anthropological, psychological, historical etc, are helpful in assessing Adventism's presence, identity and function in the world.

There remains a continuing reluctance within sectors of Adventism to evaluate their movement including Ellen White's role other than from a singular, theological perspective. Rarely has Ellen White or the movement she helped pioneer been assessed from a sociological dimension, as this may be perceived to mitigate against and/or devalue the validity of her authority and also Adventism's prophetic status. This is indeed unfortunate for both the messenger and the message are better understood through open enquiry.

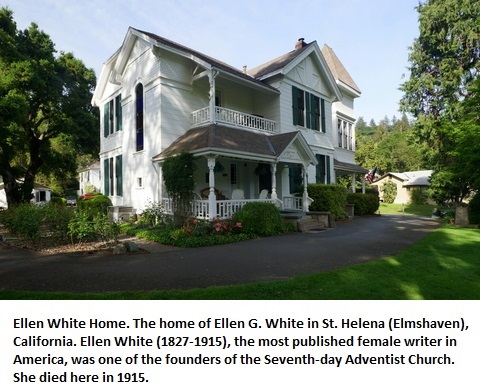

As noted above, Seventh-day Adventism emerged as a prophetic movement based around a charismatic (sociological sense) figure - Ellen G. White. Has anyone heard of Max Weber? He studied the nature of charisma and concluded that charisma is a phenomenon typical of prophetic religious movements.[3] What did he mean by 'charisma'? He defined charisma as a quality of an individual by virtue of which he/she is recognized as extraordinary and treated as endowed with supernatural qualities. These qualities are not available, however, to the ordinary person but are regarded as having a divine origin and on this basis the individual is treated as leader or prophet.[4] Visions and revelations are the primary basis for the emergence of charisma. John Wilson, in summarizing the relationship between charismatic leaders and their followers, suggests that the most important thing to recognize is that these extraordinary virtues or qualities are imputed to the leader by other people irrespective of the prophet/leaders personal divine calling. Charismatic authority is power that is legitimized, validated and consented to by those who are subject to it. Charismatic authority is functional, then, when a group consents to an individual's exercise of power because its followers regard that individual as especially gifted above all other mortals. Again, Weber underscores the pivotal relationship between the leader and those who follow:

"What alone is important is how the individual is actually regarded by those subject to charismatic authority, by his 'followers' or 'disciples' . . . It is recognition on the part of those subject to authority which is decisive for the validity of charisma." [5]

Clearly, the role of the religious community who support the prophet/leader is vital for a prophet cannot function or exist in a vacuum. It is not the divine prophetic call on its own that is important, but the role of the followers in recognizing and supporting that "call." These concepts have important implications for prophetically led religious movements - including Adventism. Consideration now needs to be given to the ways in which Ellen White's charisma was understood, legitimized and routinised by the Sabbatarian Adventists and later Seventh-day Adventists.

Seventh-day Adventist Identity: Prophetic Legitimacy

Adventism has expended much more time concentrating on the prophetic 'divine call' than on the human response of the followers in supporting that call. A leader can only request - an authority can require. The notion of legitimacy is not coercive power but involves a measure of voluntary submission.[6] The use of the term 'leadership' as opposed to 'authority' defines the relationship of duty between the charismatic leader and those who follow. It is at this point that charisma and legitimacy meet. The leader is unable to refuse the call by a higher power - the followers of charisma are duty-bound to obey the leader. It is when recognition is transformed from a cursory interest to ethical duty that the charismatic prophet/leader obtains legitimacy. Wolfgramm stated that the prophet obtains legitimacy when recognition is transformed from temporary interest to duty.[7]

Thus, the charismatic prophet requires validation, duty, devotion and obedience which are freely given on the basis that the prophet/leader continues to prove himself/herself by exhibitions or exceptional powers including visions, revelations, etc. Douglas has highlighted the essential ingredient between the prophet and their contemporaries:

"One can only imagine the carefulness of trust required by contemporaries during the time prophets were establishing their prophetic role. Consequently, the affirmation of contemporaries who knew the prophet and, his or her ministry should be prime witnesses to the prophet's credibility or lack of it." [8]

Prophets, almost without exception base their claims to leadership on supernatural revelation and the divine personal call.[9] As a result of this special calling, continual and external proofs must be offered to the followers in the form of miracles, predications and exposition of certain doctrines and teachings for authority to remain.

There is always, therefore, an interdependent relationship between the leading and following elements in charismatic phenomenon. To speak of charisma without disciples is akin to sailing a boat without water. Thus, an unrecognized prophet/leader is a contradiction of terms.[10] A prophet's legitimacy remains intact, however, only as long as belief in its charismatic inspiration remains. This is why Adventism has experienced ongoing controversies over the role of its prophet/leader Ellen White throughout its history. To summarise, two central points are recognized with respect to acknowledging charismatic authority. First, legitimacy is initially contingent on demonstrations (miracles, visions, revelations) and secondly, if legitimacy is to continue, on duty.

Ascribing legitimate authority and status to a potential possessor of charisma is based initially on the unstable and often transitory nature of the bearer of charisma's demonstration of proofs. Once those proofs have been accepted by the followers of the prophet, a transformation occurs wherein the disciples are duty-bound to accept the prophet as legitimate and authentic. Once this occurs the relationship tends to stabilize and routinisation commences.

Seventh-day Adventist Identity: Charismatic Routinisation.

As mentioned previously, charisma is a phenomenon typical of prophetic movements in their early stages, but as soon as the position of authority is established the young religious movement begins to give way to routine. This is exactly what transpired with the early church following Pentecost. Following the conversions of thousands of people, the logical question to ask is "what do we now do to care for these new believers and what measures need to be taken to continue the new movement?" As soon as these questions are contemplated - routinisation has commenced. Why does this occur? Those who witness the new movement and seek to continue it wish to secure the permanence and viability of the originating charisma into the future. The prophet's personal charisma is not transferable however, hence, a group led by a charismatic leader will tend to routinise by establishing structures, organizations and institutions to carry on the prophet's originating visions and instructions. Thus, as soon as a dedicated band of disciples desire identity, structure, continuity and security - original prophetic charisma is replaced by the rule of routine, everyday life - routinisation is underway. To state it another way - whenever the loss of the emergency character out of which charismatic authority germinates, the character of a permanent institution is assumed.

During the 1840s and 1850s, the co-founders of Seventh-day Adventism, Ellen and James White along with Joseph Bates, could not have comprehended the incredible development of a movement they helped create. In their search for sanity, consolation, unity, and truth through the convening of Sabbath conferences and spreading the printed page, coupled with extensive visitations, they had in fact put in place the initial organisational framework that would gradually evolve into a worldwide movement. While Ellen White and her devoted followers did not initially recognise the full significance of her first vision in December 1844, a further vision four years later (November 1848) would signify that the 1844 crisis was well in the past and that a compelling purpose for the movement's existence was in place. The process of routinisation was underway; a new movement was developing and there was no turning back.

The Sabbatarian Adventists' emerging identity based on their developing theology created the necessity for further organisation, although options remained limited. They may have opted to deny their past experience along with the majority of Millerite believers and become absorbed back into the general society including a number of organised religious groups. Alternatively, they may remain true to their convictions based on White's visions, that God had more in store for the "little flock." The experience of the early pioneer Sabbatarians resonates with Weber's thesis of routinisation of charisma:

"In its pure form charismatic authority has a character specifically foreign to everyday routine structures. The social relationships directly involved are strictly personal, based on the validity and practice of charismatic personal qualities. If this is not to remain a purely transitory phenomenon, but to take on the character of a permanent relationship forming a stable community of disciples or a band of followers or a party organization, it is necessary for the character of charismatic authority to become radically changed. Indeed, in its pure form charismatic authority may be said to exist only in the process of originating. It cannot remain stable, but becomes either traditionalized or rationalized, or a combination of both." [11]

Routinisation, therefore, commences in principle with the very establishment of the charismatic community. This is particularly apparent in social movements that aim to recruit new members. Something must be done to accommodate these new members; they must be initiated into, nurtured and to some extent "controlled by the movement."[12] Furthermore, routinisation not only involves a transition from spontaneity and fluidity towards organisational routine and order, but also operates at the level of ideology; thus, "charismatic pronouncements are gradually codified and systematized."[13] The elaboration and codification of doctrine eventually assumes its own legitimacy and often becomes immovable "tradition." This is why charisma and formalism are opposed. This situation also provides a rationale as to why change is difficult to address in ageing religious communities and why formalisation is fundamentally opposed to new initiatives or enterprises. The implications of doctrinal codification and tradition remain a significant "pressure point" within contemporary Adventism.

Adventism, therefore, continues to experience the tensions between sectarian impulses and denominationalising tendencies.

Seventh-day Adventist Identity: A Denominationalising Sect?

"Many new religious bodies are created by schisms-they break off from other religious organizations. Such new religions commonly are called sects. Many other new religious bodies do not arise through schisms; they represent religious innovation. Someone has a novel religious insight and recruits others to the faith." [14]

As sectarian movements develop and mature, they tend to accommodate themselves to the society against which they originally opposed and in the process, proceed towards institutionalisation. H. R. Niebuhr suggested that a sect is essentially an unstable religious organisation that over time, tends to transform into a church. Following this transformation, member's needs originally satisfied by the sect, no longer find the same measure of fulfilment in the church. Over time this leads to discontent, which in turn prompts further schism and the hiving off a new sect. Have you ever wondered why Adventism has felt the impact of numerous antagonistic independent ministries that believe the movement has apostatised? Divergent theological views alone do not constitute the reason, irrespective of those who sincerely believe they do.

In An Analysis of Sect Development, Bryan Wilson cites several broad characteristics that are useful in identifying differences between sects and denominations. All sectarian movements are limited in their organisational style by their theological convictions and commitments, maintaining separation from the world in varying degrees, with sect members always distinguishable from outsiders in relation to "doctrines, practices, forbearances and by disassociation in some respect or other, from the ways of the world."[15] Adventist sects, in particular, are disposed to discount any form of organisation on the basis that their major preoccupation with the imminent Advent of Christ should not be impeded by mundane and routine earthly organisational dilemmas. Time, energy and resources expended on organisation are deflected for more urgent purposes, making minimal organisation idyllic. If some form of organisation is required, it is for the purpose of promulgating the message in the hope of proselytising people.

Typically, a sect is a voluntary association with membership subject to some claim of personal merit, be it knowledge of doctrine, recommendation of existing members in good standing or affirmation of a conversion experience. Exclusiveness is both emphasised and encouraged, with expulsion held over against those who contravene moral, doctrinal or organisational precepts. The sect's self-designation is centred in their self-concept of uniqueness, that is, an elect remnant possessing special enlightenment. Personal perfection is the expected standard of aspiration and the priesthood of all believers is accepted as the ideal, with a high level of lay participation encouraged. Ample opportunity is afforded for members to spontaneously express their commitment to the group and sects pursue a totalitarian rather than segmental hold over their members. In doing so, they either dictate the member's ideological orientation to secular society or they meticulously specify the obligatory standards of moral and ethical rectitude, or they coerce the member's involvement in group activities. The sect remains either hostile or indifferent to the state and secular society in which it is born.[16]

The denomination, on the other hand, exhibits a number of contrasting features. Essentially it is a voluntary association and accepts adherents without traditional prerequisites or imposition and employs formalised procedures of admission. Both tolerance and breadth are emphasised and since membership is relatively uncontrolled, expulsion is not a commonly employed device for dealing with the apathetic or wayward believer. Self-perceptions of uniqueness are generally underplayed, with individual denominations content to be considered one among many. Doctrinal differences are generally minimised as they are considered to be all equally acceptable in the eyes of God and the standards of the prevailing culture and conventional morality are accepted. Trained professional ministry is a central feature, while lay participation is restricted to designated areas of activity. Worship services are formalised and lack of spontaneity is evident; evangelism to outsiders takes a "back seat" to educational programmes for the young and additional church activities are largely non-religious in character and content. Individual commitment lacks intensity and the denomination accepts without regard, values that are drawn from most sections of society and state, while all of society provides the membership pool.[17]

Tarling, in his book, The Edges of Seventh-day Adventism,[18] argues that the essential differences between a sect and a denomination are both sociological and theological and can be expressed as follows: 1) A sect's followers are largely drawn from the poorer classes; a denomination's followers tend to be higher on the socio-economic scale. 2) A sect is a small, unstructured group; a denomination is institutionalised. 3) A sect sees itself as the exclusive community of the saved; a denomination believes the saved are also in other fellowships. 4) Pioneers of the sect are seldom schooled in theology; a denomination runs theological seminaries. 5) A sect is almost always against the establishment; a denomination draws on the establishment for support. 6) A sect owns little or no real estate; a denomination has a wide diversity of properties and investments. 7) Sects group themselves around a charismatic leader; in a denomination, charismatic personalities often clash with church leadership. 8) A sect's members adhere to a unified (though not necessarily written) code of beliefs; a denomination has a wide range of beliefs among its followers (even though it may have a creed). 9) A sect has an extra-Scriptural source of authority; a denomination does not. 10) A Christian sect is often non-Trinitarian; a denomination believes in the Father, the Son and the Holy Ghost as equal in the Godhead (although this should not be considered time bound, as is the case when Reformation and Counter Reformation orthodoxy ceases to be the norm).

Further elaboration on the sect/denomination experience in Adventism along with the impact of charismatic routinisation and Ellen White provides food for thought.

SDA Identity: A Continuing Dialog

In the pages above, focus has been provided on SDA identity including concepts such as charisma, legitimacy, charismatic routinisation and sect/church typologies. I will now attempt to briefly focus on how these concepts have impacted on the development of the SDA movement.

As has been noted, the primary method is assessing SDA identity has been limited to a theological perspective which has served to ignore the impact of sociological forces on and in the movement. A religious movement's belief system often provides minimal comment on that same movement's actual existence in society. Theology alone is incapable of analyzing Adventism's sojourn in society. What a church "says" and "does" are not mutually inclusive. Tensions are often inherent and discernable.

Mid-19th century America was a period of history during which a number of religious movements were birthed amidst numerous political, social, scientific and cultural upheavals. Millennial movements were not uncommon during these times and generally arose in search of a new society with new orders, new ideals, new standards, and a new prophet to organize these new assumptions and articulate them. It has been observed that charisma is unable to exist independently of the charismatic leader and the followers of Ellen White arose out of a collective, communal response within a specific context, most notably, at a time of crisis. The Great Disappointment in 1844 provided fertile soil for the Millerite movement in which the charismatic gift could flourish; it provided the milieu for the reception of Ellen White's charismatic legitimacy. Ultimately, Ellen White's leadership, above all, served to calm the religious intensity and encourage the scattered and shattered Sabbatarian Adventist believers into eventually becoming an organized movement.

Within two months of the Great Disappointment (22 October 1844) Ellen White, in embryonic form inaugurated the process that would routinise her personal charisma. This was achieved primarily through visionary experiences declaring that the Millerite movement was not the end; rather, it constituted a stepping stone and a trial through which the remnant must pass on their way to the heavenly city. These revelations confirmed in the minds and hearts of White's followers that she was indeed called of God, thus legitimizing her role. These revelations also served to locate Adventism in the prophetic time stream. White's visions (including the Great Controversy Theme) painted on the Adventist canvas both broad panoramic scenes and intimate details relating to the direction in which the movement should proceed.

Consider the following:

The fledgling sectarian movement that White co-founded knew no organisational hierarchy, employed ministry was non-existent and there were no promotions, careers, appointments or dismissals. Her charismatic authority was clearly outside the realm of everyday routine and sharply opposed to rational, bureaucratic and traditional authority. Her charisma was legitimised on the basis of the supra-rational (visions) and in this sense was foreign to all conventional rules. The fact that rules eventuated was demonstrated by her marginalisation from the movement at the end of the 19th century.

While charisma is a phenomenon typical of prophetic movements in their early stages, as soon as the position of charismatic authority is established, the forces of everyday routine commence. Charismatic authority, therefore, can only exist in the process of originating. It was noted above that the routinisation of charismatic authority arises from the desire of the leader and followers that the continuation of the group be maintained as a permanent community, organisation or institution during and beyond the life of the charismatic leader. The irony of charismatic routinisation, however, is that the desire to preserve and safeguard the original charisma can only be satisfied by its transformation, phenomena readily discernable in SDA experience and one which continues to create tension between preaching Advent immanency and continuing earthly occupancy. Much of the ongoing agitation with Adventism is a result of the perceived Advent delay.

Ellen White provided the key to Adventism's eschatological timetable including the Great Disappointment. To translate her cosmic visions into everyday, earthly reality and routine, called for the cessation of the transitory nature of charisma that opposed rationality and economic gain into a phenomenon that assumed the character of a permanent, organised institution with an ever-increasing and stable membership. Adventism achieved consolidation through doctrinal development and organisational structures. While Adventist theology provided the rationale for its identity and its commission to preach the last warning message to the world, Adventist organisation provided the means to accomplish the task and in doing so created incredible tension.

Furthermore, the routinisation of Ellen White's charisma posed a monumental dilemma for Adventism in that her visions provided a rationale on which the development of SDA organisations and institutions could be established. Her GCT coupled with a restorationist ideology was intended to permeate SDA institutions with their peculiar sectarian ethos and identity. White envisaged that the establishment of organisations and institutions would prepare people spiritually, physically and mentally for the imminent parousia (regardless of how short or long imminent might be interpreted to mean).

The pressure of change (both internal and external) is monumental in religious movements founded on charisma, but it is eventually bureaucratised in the interest of orderly transmission. Growth inevitably necessitates change. To accommodate growth within Adventism, the original vibrant character of the movement was replaced by forms and structures designed for self-perpetuation. It is also evident that the emergence of these structures has caused considerable contention within the movement, particularly for the purists, who believe the integrity and identity of Adventism is being compromised. Diversity is also a result of growth, which leads to further change and contention. Seventh-day Adventism is a successful movement as a result of institutionalisation, which has also led to increased respectability in society. The irony of this transformation is that the very qualities of discipline that early Adventism in its rigor instilled, have contributed to the material success and intellectual restlessness that later revisionists have interpreted as signs of social decadence and theological heresy.

While Adventism continues to retain a number of distinctive traits that provide for the continuation of its sectarianism (i.e., Sabbath worship, theological posturing and Ellen White as a unique source of revelation), other dimensions of Adventism stoutly favour evolution towards denominationalism. These dimensions include a full time professional ministry, tertiary degrees and training for numerous professions, development of educational and health institutions that, in turn, staff schools, colleges, universities and hospitals and, as well, foster increasing upward mobility. In addition to these endeavours, publishing houses, health food companies, radio and television communication centres have all evolved in response to the movement's evangelistic ideals on the basis of White's counsel.

Herein lies Adventism's paradox. In its desire to construct unique sectarian institutions conducive to separation from the world as a result of charismatic routinisation and then to utilise those same institutions to evangelise the world, Seventh-day Adventism has become poised between two conflicting extremes. The means (institution building) adopted in the attempt to reach Adventism's desired end (successful evangelism) appears to have denied the movement's explicit reason for its existence (preaching the imminent parousia). Thus, a major dilemma facing Seventh-day Adventism is whether temporal goals are displacing ultimate Advent goals.

The routinisation of White's charisma, however, initiated the process of institutionalisation within Adventism and in the process altered the nature of SDA identity. No longer is it appropriate to isolate Adventism's belief system from its conduct in the world, for both doctrine and deed operate simultaneously. In other words, SDA identity consists of more than the sum of its collective beliefs. From a pragmatic perspective, action detached from belief must decline in effectiveness resulting in increased nominalism. This brief study has argued that content (beliefs) and form (structures) must be analysed concurrently rather than being isolated into matters of content or belief alone. Any determination, therefore, of Adventism's identity must include both beliefs and structures. It appears certain, that up to the present time, the Seventh-day Adventist church has concentrated on the "truth" of belief at the expense of giving adequate attention to the "truth" of structure. In terms of identity, what SDAs incarnate is equally important as what they articulate.

Dr Rick Ferret

Lecturer

Avondale University, NSW

Australia

[1] Hammill, R, I. (1992). Pilgrimage: Memoirs of an Adventist Administrator. Berrien Springs, MI: Andrews University Press, p. 233.

[2] Theobald, R. (1985). "From Rural Populism to Practical Christianity: The Modernization of the Seventh-day Adventist Movement." Archives de Sciences Sociales des Religions, 60(1): 109-130.

[3] Weber, M. (1947). The Theory of Social and Economic Organization. T. Parsons (Trans.). New York: Free Press, p. 370.

[4] Weber, 1947. pp. 241-242.

[5] Weber, 1947. p. 359.

[6] Weber, M. (1964). The Theory of Social and Economic Organization. New York: Free Press. pp. 324, 325).

[7] Wolfgramm, R. (1983). Charismatic Deligitimation in a Sect: Ellen White and Her Critics. M.A. dissertation, Chisholm Institute of Technology, Canberra, Australia. p. 22.

[8] Douglass, H. E. (1998). Messenger of the Lord: The Prophetic Ministry of Ellen G. White. Nampa, ID: Pacific Press Publishing Association. p. 29.

[9] Weber, M. (1968). On Charisma and Institution Building. S.N. Eisenstadt (Ed.). Chicago: University of Chicago Press. p. 253.

[10] Wilson, J. (1978). Religion in American Society. New Jersey: Prentice Hall. p. 111.

[11] Weber, 1947, pp. 363, 364.

[12] Theobald, R. (1979). The Seventh-day Adventist Movement. A Sociological Study with Particular Reference to Great Britain. Ph.D. dissertation supplied by the British Library Document Supply centre. p. 169.

[13] Theobald, 1979, p. 169.

[14] Stark, R., & Bainbridge, W. S. (1985). The Future of Religion: Secularization, Revival and Cult Formation. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. p. 19.

[15] Wilson, B. R. (1967). "An Analysis of Sect Development." In B. R. Wilson (Ed.). Patterns of Sectarianism: Organization and Ideology in Social and Religious Movements. (22-45). London: Heinemann Educational Books Ltd. p. 28.

[16] Wilson, 1967, pp. 23, 24.

[17] Wilson, 1967, p. 25.

[18] Tarling, L. (1982). The Edges of Seventh-day Adventism. Barragga Bay, Bermagui, South Australia: Galilee. pp. 2, 3.

Home > Online Magazine > Online Magazine: Edition 81 - Spring (Sep-Nov) 2024 > Seventh-day Adventist Identity (Deed or Creed) (by Dr Rick Ferret)

Copyright © 2024 Thornleigh Seventh-day Adventist Church